Apollo Command and Service modules

Zond with L3 stage in assembly hanger

artist's concept of the THEMIS A, B, C, D, E spacecraft in orbit (aka ARTEMIS)

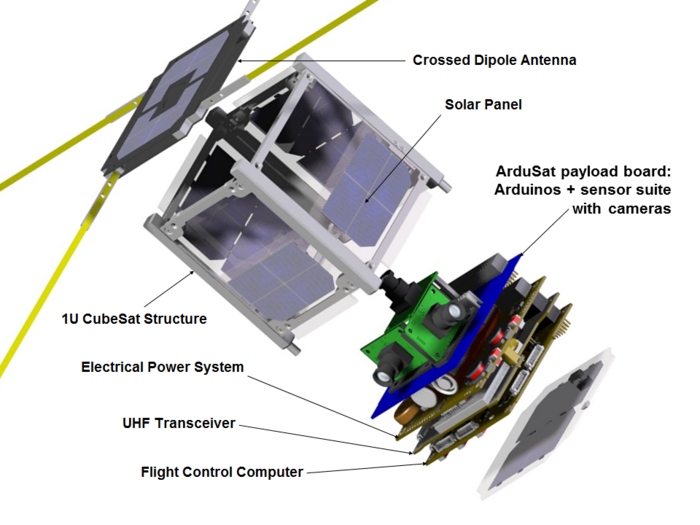

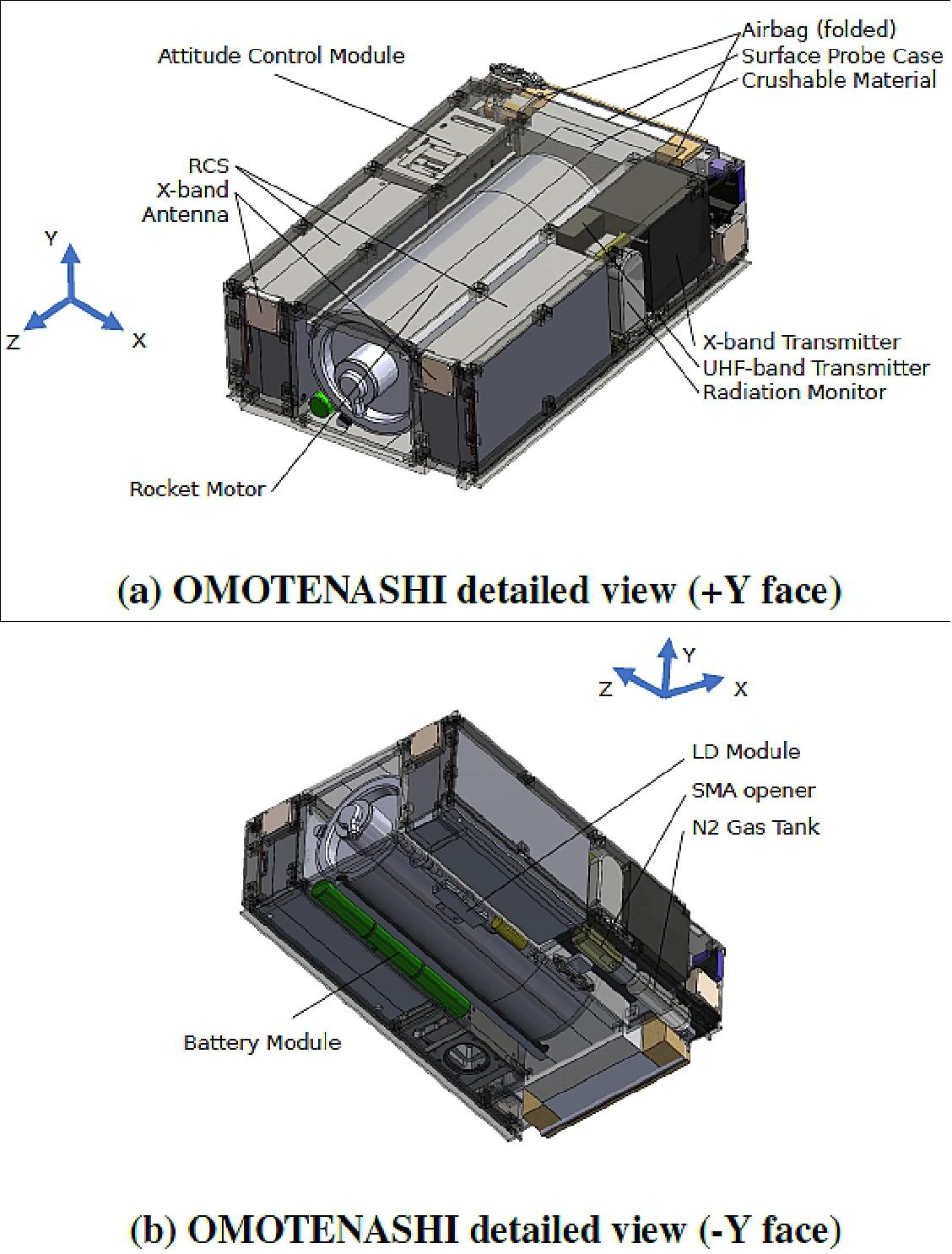

1U ArduSat CubeSat and proposed 6U OMOTENASHI CubeSat

A spacecraft is a vehicle, or machine designed to fly in outer space. A spacecraft that only orbits Earth is typically called a satellite. For the US Apollo program to the Moon the spacecraft included the Apollo command module, service module, and lunar module. For the USSR Zond program to the Moon the Zond spacecraft was a stripped-down Soyuz 7K-L1. For the USSR N1/L3 program to the Moon the spacecraft would have included a Soyuz 7K-L3 or ("Lunniy Orbitalny Korabl", LOK), and a lunar lander or ("Lunniy Korabl", LK).

The Apollo, Zond, and N1/L3 spacecraft were designed to carry humans or animals, providing them with needs such as oxygen and water, and protecting them from heat, cold, and radiation of the space environment. The Apollo spacecraft would spin in order to change what side was facing the sun and thus distribute the heating more evenly. They and other spacecraft also provide navigation and guidance and attitude control in order to reach their destination with a minimum amount of fuel for course correction.

Most parts in spacecraft operate best between -5 and 40 degrees Celsius (20 and 120 Fahrenheit). In space, a spacecraft recieves heat directly from the Sun. To prevent the temperature from getting too high, a spacecraft must be able to eliminate excess thermal energy. Likewise, when it gets too cold a spacecraft must be able to heat itself. The simplest way to manage temperatures is by using passive thermal control systems that do not require any additional power. However, it might be necessary to use active systems such as heaters or cooling fluids pumped through the system.

If a spacecraft is to point itself in the right direction it needs to know where it is and how it is oriented in space. Common forms of navigation for spacecraft include celestial navigation, inertial navigation, and radio navigation. For celestial navigation, 'Sun sensors' indicate to a spacecraft the direction of the Sun. Similarly, 'star tracker's are optical sensors that can be used to detect a single star. Star trackers are usually used on three-axis stabilized spacecraft or on de-spun platforms of spinning spacecraft. For inertial navigation, gyroscopes tell a spaecraft the directions and velocities of its own rotations, but do not indicate orientation in space. By starting with a known attitude, and by tracking rotation using gyroscopes, the spacecraft can track its attitude while moving. Gyroscopes are often combined with accelerometers in Inertial Measurement Units or IMUs. IMUs typically have three gyroscope axis and three accelerometers, one combination of each for each spacecraft axis. Radio navigation uses direction, travel time, and doppler shift of radio signals from a base statation to determine the direction, distance, and velocity of a spacecraft. Apollo used all three of these forms of navigation.

A spacecraft also needs to control its orientation or attitude while moving through space. There are two main approaches to control the attitude of a spacecraft: spin stabilized or three-axis stabilized. Spin stabilization works by spinning the spacecraft like a top. Spin stabilization is very efficient, and little power or rocket thrust is needed to maintain a particular attitude. The downside of spin stabilization is that all the sensors are also spinning, making it difficult to point cameras, or orient antennas and solar arrays.

Many spacecraft are three-axis stabilized, which means their attitude is actively controlled around all three rotational axes. Nearly all three-axis stabilized spacecraft have a reaction control system consisting of small rocket thrusters distributed around the spacecraft. Another method for three-axis stabilitzation is the use of electrically powered reaction wheels. If a reaction wheel is set in motion with an electric motor, not only will the reaction wheel start to rotate, but the spacecraft itself will also begin to rotate in the opposite direction. Since a spacecraft has three orthogonal axes around which it can rotate, it can be controlled by three of these reaction wheels. While Apollo would spin in order to distribute heating, it used a reaction control system consisting of a series of small rocket thrusters for attitude control.

| Spacecraft | mission type | country of development | launch system | guidance control system technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luna 2 | Lunar impactor | USSR | Luna 8K72 variant of R-7 Semyorka | |

| Ranger 7, 8, 9 | Lunar impactor | USA | Atlas LV-3 Agena-B | |

| Luna 9, 13 | Lunar lander | USSR | Molniya-M 8K78M | |

| Luna 10, 11, 12, 14 | Lunar orbiter | USSR | Molniya-M 8K78M | |

| Surveyor 1, 3, 5, 6, 7 | Lunar lander | USA | Atlas SLV-3C Centaur-D | no onboard computer, command remote control (R/C) by humans |

| Lunar Orbiter 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | Lunar orbiter | USA | Atlas SLV-3 Agena-D | |

| Explorer 35 | Lunar orbiter | USA | Delta E1 | |

| Zond 5, 6, 7, 8 (aka Soyuz 7K-L1) | circumlunar trajectory and return | USSR | Proton-K/D | Argon-11C (sometimes listed as Argon-11S ?) |

| Apollo 8, 10 | Lunar orbiter and return | USA | Saturn V | Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC architecture) |

| Apollo 11, 12, 14 | Lunar orbiter and lander and sample return | USA | Saturn V | Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC architecture) |

| Luna 16, 20, 23, 24 | Lunar lander and sample return | USSR | Proton-K/D | |

| Luna 17, 21 / Lunokhod 1, 2 | Lunar lander and rover | USSR | Proton 8K82K with Blok D upper stage | |

| Luna 19, 22 | Lunar orbiter | USSR | Proton-K/D | |

| Apollo 15, 16, 17 / with Lunar Rover | Lunar orbiter and lander and rover and sample return | USA | Saturn V | Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC architecture) |

| Explorer 49 | Lunar orbiter | USA | Delta 1913 | |

| Hiten (MUSES-A) | Lunar orbiter | Japan | Mu-3S-II | three HD68HC000 (aka 68k) (68000 architecture) |

| Clementine | Lunar orbiter | USA | Titan II(23)G | 1750 (MIL-STD-1750A architecture) |

| Lunar Prospector | Lunar orbiter | USA | Athena II | no onboard computer, command remote control (R/C) by humans |

| SMART-1 | Lunar orbiter | ESA | Ariane 5G | Atmel TCS695E single-chip ERC32 (SPARC architecture) |

| ARTEMIS P1, P2 (THEMIS B, C) | Lunar orbiter | USA | Delta II 7925 | low-power 8085 (8080 architecture) |

| SELENE (Kaguya) | Lunar orbiter | Japan | H-IIA | SuperH SH-3 (SuperH architecture) |

| Chang'e 1, 2 | Lunar orbiter | China | Chang Zheng 3 | |

| Chandrayaan 1 | Lunar orbiter | India | PSLV-XL | LEON 3FT-RTAX (SPARC architecture) |

| Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter | Lunar orbiter | USA | Atlas V 401 | RAD750 (POWER architecture) |

| LCROSS | Lunar impacter | USA | Atlas V 401 | RAD750 (POWER architecture) |

| GRAIL A, B | Lunar orbiter | USA | Delta II 7920H | RAD750 (POWER architecture) |

| LADEE | Lunar orbiter | USA | Minotaur V | RAD750 (POWER architecture) |

| Chang'e 3, 4 / Yutu-1, 2 | Lunar lander and rover | China | Long March 3B | |

| Queqiao, Longjiang-1, 2 | Lunar orbiter | China | Long March 4C | |

| Chandrayaan 2, 3 / Vikram / Pragyan | Lunar orbiter and lander and rover | India | GSLV Mark III M1 | |

| Chang'e 5 | Lunar lander and sample return | China | Long March 5 | |

| CAPSTONE | Lunar orbiter | USA | Electron | |

| Danuri | Lunar orbiter | Korea | Falcon 9 | |

| Artemis 1 | Lunar orbiter and return | USA | SLS Block 1 | |

| SLIM / LEV-1 and LEV-2 | Lunar orbiter and lander and rover | Japan | H-IIA | PowerPC (POWER architecture) |

| Nova-C Odysseus IM-1 | Lunar orbiter then lander | USA | Falcon 9 | |

| Blue Ghost M-1 | Lunar lander | USA | Falcon 9 |

CubeSats are small and light weight satellites that use an open source architecture based on a 10 x 10 x 11.35 cm cube of about 2 kg. Earth orbiting CubeSats quite often don't have attitude control at all. They're designed to have antennas and solar arrays work when oriented in almost any direction similar in some ways to spin stabilized spacecraft. An example of this would be the Earth orbiting 1U ArduSat CubeSat. However, this wouldn't work for the proposed 6U OMOTENASHI CubeSat which is intended to land on the Moon. In cases like this, miniaturized gyroscopes, accelerometers, reaction wheels, and thrusters have to be designed to track and control the CubeSats attitude.

GNC Subsystems used in CubeSats

- Reaction Wheels

- Star Trackers

- Sun Sensors

- Earth Sensors

- Inertial Sensors (Gyroscopes & Accelerometers

- GPS Receivers

- Magnetic Torquers